Why knowing is never enough to change a behaviour

- vikstevens

- Dec 18, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 20

Knowing is only an illusion when it comes to behavioural and habit change. Three strategies are provided to help you to transform your life-enhancing goals into actionable achievement.

I ought to eat healthier, get better sleep, exercise more, consume less, meditate... the list goes on. We've all heard these promises and made them to ourselves. Healthy habits are fundamental health knowledge, widely recognized and undisputed.

We are all well aware of the health benefits both mentally and physically, but why do we keep pushing health goals back? Why is it that even when we have the knowledge to improve our lifestyles, it is never enough to get us to where we want to be?

"Knowing" is only an illusion

Recent work in cognitive science has demonstrated that knowing is only a small piece of the equation for most real world decisions.

Let’s use this simple visual optical illusion as an example.

The Mueller-Lyer Illusion: Two parallel lines, one with fins facing inward, the other with fins facing out. Most North Americans say that the line with the outward facing fins is larger than the other line.

We may know (or find out after measuring) that these two lines are the same length. However, even when we know they are the same length, our eyes and minds still might trick us to think that the first line is longer.

We may also know that a tasty piece of fudge shaped like cat poop will taste delicious but we’ll still be pretty hesitant to eat it. Additionally, we may know that $19.99 is relatively the same price as $20.00, but we still lean towards the cheaper item.

The issue lies in the illusion that knowing something equates to mastering it. We may read books, articles, watch an inspiring TV show or listen to a motivating podcast and feel as though understanding it basically improves our lives, but in reality it is much more difficult.

Habits are deeply ingrained

Behaviour change is so difficult because of internal and external reasons. Internally, we are a creature of habit. We don’t need to give too much thought to many of our daily routines. We let our automatic pilot switch on as we hear our alarm clock go off in the morning. We get out of bed, brush our teeth, get dressed and have breakfast. We go through the day's motions and repeat a similar reverse routine as we get ready for bed at night. A habit or behaviour change requires breaking out of familiar patterns, which demands effort and self-awareness. Externally, our social and physical environment usually work against positive change. Whether it be social media algorithms with endless scrolling feed, or great deals nudging us to get the bigger size meal or the easily accessible elevator in a building to get us to the second floor, we must work extremely hard and go out of our way to achieve our health goal.

Steps toward positive change

The real power of behaviour change comes not from knowledge, but from things like situation selection, habit formation, and emotion regulation. To create a meaningful change, it requires rigorous effort, persistence, and often a willingness to rewire rooted behaviours.

In Occupational Therapy, we use the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) or Stages of Change to guide clients through five stages of behaviour change. While the first two steps (contemplation and preparation) are essential for effective change, the major effort lies in the third (Action) and fourth stage (Maintenance). Think of it as climbing Mount Everest. We start off with energy, motivation and all the will-power to reach our goal (getting to the summit). We do our preparation; we have the appropriate equipment, the map and all essential knowledge to get started. Our legs are fresh and the vertical is gradual. As we get to the last two stages of the climb, we are more tired, the air contains less oxygen, the climb is steeper and weather is less forgiving. Internal and external reasons come to play. This is where we have to really dig deep and focus on our goal.

⬍ Precontemplation (no intention to change)

⬍Contemplation (considering change)

⬍Preparation (planning for change)

⬍Action (making the change)

⬍Maintenance (sustaining the change)

3 Strategies to help transform knowledge into action:

While behavioural change is often an individualized approach based on a person’s environment, daily activities and personal abilities, here are three strategies, grounded in behavioural science, that can serve as a starting point.

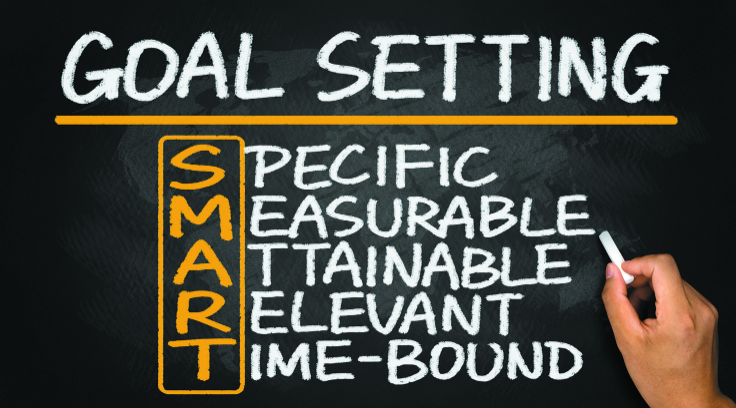

Use a “SMART” goal:

Start thinking in terms of a “SMART” goal. This will help align your true reasons and purpose behind change to actually create a meaningful difference and help keep consistency in the future.

Specific: What is it exactly you want to achieve? Sure, maybe you want to exercise more but do you want to exercise more to complete a marathon? Do you want to exercise to bring down your blood sugar levels? Do you want to exercise to increase your mood? If the goal is too general it will unlikely be successful. Try to think in terms of specifically why you would like to adopt a new habit or let go of an old one.

Ex: instead of “exercise more” aim to “increase my heart rate by walking daily”

Measurable: How will you measure this goal? Will you have a tracking sheet on your fridge? A journal with your daily progress? Measuring your progress will help you keep accountable and help determine if some readjustment is needed along the way.

Attainable: How realistic is this goal? Experts like James Clear (Atomic Habits) and B.J. Fogg (Tiny Habits) emphasize the importance of starting with small, manageable actions. Instead of reading for an hour every day, start with 5 minutes. This will help kick-start a new micro-habit as we obtain a sense of accomplishment which can eventually turn into significant change.

Relevant: Why is this goal important to you? Does it align with a greater personal goal? Reflecting on these questions will help determine the likelihood of the goal achievement.

Time-bound: When will you achieve this goal? Or if you are breaking down this goal even further, how much time weekly, daily will you put into this? By setting a deadline or a precise amount of time, it helps create a sense of urgency and focus towards this goal.

See visual poster for "SMART" goal: https://www.stevensot.com/re

Habit Stacking method:

When we feel overwhelmed, we don’t know where to start and will likely not do anything at all towards actioning change. Internal and external factors may get easily in the way and we will just keep putting it off. The goal is to reduce friction so that our brain has no excuse to resist. Habit stacking is an efficient way to pair a new habit with an existing habit like brushing your teeth or making breakfast. It makes it easier to remember to practice the new activity.

Example: Try using: “After/during/while/before/in between ____ (current habit)___, I will ___ (new habit)___.”

Example of a SMART goal + Habit Stacking = After my alarm goes off in the morning, I will practice guided meditation for 5 minutes, 5 days a week for the next 30 days using a guided app to help reduce stress.

Optimize your physical environment:

Visual cue as a helper!

“Out of sight, out of mind”. This proverbial meaning does come to play when we are trying to ignore or forget about something. Want to eat healthier? Get those darn tasty cookies out of sight. Wansink et al. (2016), have in fact demonstrated how environmental factors (specifically the types of food visible on the kitchen counter) influences eating habits and health. The presence of fruit on the counter was associated with a lower BMI. The opposite is also true when helping us integrate a new habit. Want to play more guitar? Get it out of the closet and have it sit in the living room. This visual cue will help remind you of your goal and you will likely pick it up more as you’re playing with your kids, have an extra 5 minutes before leaving the house or reach for the guitar versus the remote control. Want to exercise more? Why not put a pair of dumbbells in your bathroom and do a few biceps curls after each time you go pee? These simple environmental tweaks reduce the cognitive load of thinking of the new habit and increase the likelihood of actually practicing it. Therefore, visibility and convenience both matter when trying to eliminate an unhealthy habit or integrate a new one!

While there exist more various strategies than the ones presented to help put knowledge into actionable changes these three strategies are good ones to start with. Now that you’ve reached the “knowing” stage, what next steps will you take to transform your life-enhancing goals into actionable achievement?

References:

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: Tiny changes, remarkable results. Avery.

Fogg, B.J. (2021). Tiny Habits. The Small Changes That Change Everything. Harvest.

Wansink, B., Hanks, A.S., & Kaipainen, K. (2016). Slim by Design: Kitchen Counter Correlates of Obesity. National Library of Medicine, 43(5), 552-558.

Comments